Peter Luty 1812-1852

The very day we landed upon the Fatal Shore,

The planters stood around us, full twenty score or more;

They ranked us up like horses and sold us out of hand,

They chained us up to pull the plough, upon Van Diemen’s Land.

Chapter 1. Peter’s Background

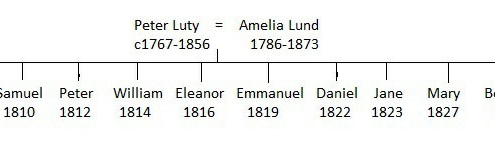

Peter’s Father & Mother Amelia’s Twelve Children

Peter Luty was born in Yeadon on 24 April 1812. He was the fourth of twelve children born to Peter Luty and Amelia nee Lund.

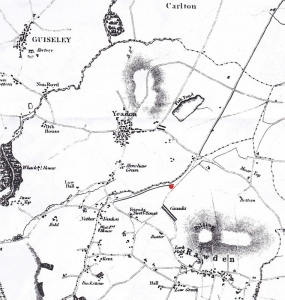

Peter and Amelia had married at Fewston church in 1804 and moved to Yeadon shortly afterwards. I am assuming that they moved for work. Yeadon Moor was enclosed in the early nineteenth century and Peter worked as a stone waller. Many of Peter and Amelia’s children worked as stone wallers in the area between Rawdon, Yeadon, Guiseley and Otley during the first half of the nineteenth century.

Yeadon had a reputation for being quite a rough place in the first part of the nineteenth century. A directory published in the 1830s describes it in these terms:

“Yeadon … on a lofty moorland hill, on the north side of Airedale ….. is a large clothing village ….. Most of the inhabitants are small clothiers, not remarkable for the politeness of their manners.”1

This item appeared in a Leeds newspaper in the 1830s2:

PARDON ASKED – Whereas we, SAMUEL LEUTY of Guiseley, and DAVID LONG, of Rawden did, on the 19th February last, assault and strike Thomas Booth, of Rawden, without Provocation, for which Offence he has commenced Prosecution against us, but in Consideration of our publicly asking Pardon, and paying all Expenses, he has kindly consented to forego the same. We, therefore, humbly ask Pardon of the said Thomas Booth, thank him for his Lenity, and promise not to be guilty again.

As Witness our Hands this First of March, 1837

Saml. LEUTY, his X Mark.

DAVID LONG, his X Mark.

Witness, W. GRIMSHAW

Samuel Luty was Peter’s brother and David Long was the husband of Peter’s sister Eleanor.

At the end of 1832 Peter and Amelia’s oldest child, John, had married and their youngest child was about three months old (but would die in the July of 1833).

The other children, ranging in age from twenty-five down to two years old were still with the family who were living at the top end of Green Lane in Rawdon. Although their house was officially in Rawdon township, it was actually as near to Yeadon village as it was to the village of Rawdon.

Red marker shows position of family home at the top of Green Lane in Rawdon.

I do not know exactly what work Peter was doing at the time. He was later described as a farmer, but I think he would more likely have been working as a farm labourer, or working with his father building dry stone walls.

- White’s Directory of the West Riding of Yorkshire 1838

- Leeds Mercury, 4th March 1837.

Chapter 2. His Trial & Imprisonment

In 1832 Peter was arrested, charged with theft and committed for trial at York Assizes.

The assizes were held at York Castle, which was also the location of the prison and the debtors prison. The buildings are still there next to Clifford’s Tower, but now house the York Castle Museum.

York Castle

The prison buildings to the right of Clifford’s Tower would not have been in use when Peter was there. They were begun in 1825, but not completed until 1835; they were demolished in the 1930s.

The wall surrounding the whole complex was not the remains of the original castle walls, but a new wall erected at the same time as the new prison block. It surrounded the whole complex including Clifford’s Tower.

This map is from around 1850.

The trial took place on 2 March 1833 and the court records read as follows:

“Peter Lewty aged 20 years and William Walker aged 22 years late of Rawden, in the West Riding, charged with having, on 23rd day of November last, on the highway in the township of Carlton, in the said Riding, assaulted William Pickles, waggoner, and feloniously stolen from his person one sovereign and five shillings in silver, and with having feloniously stolen and taken from his wagon, one box containing a quantity of linen, clothes and apparel, the in his custody.”

The verdict was recorded as follows: “Peter Lewty, Guilty of larceny, to be severally transported beyond the seas for the term of seven years”. William Walker was also found guilty of housebreaking and was sentenced to death. However, this was commuted to life and he was transported to New South Wales in June 1833.

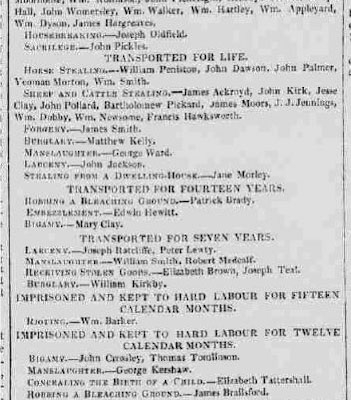

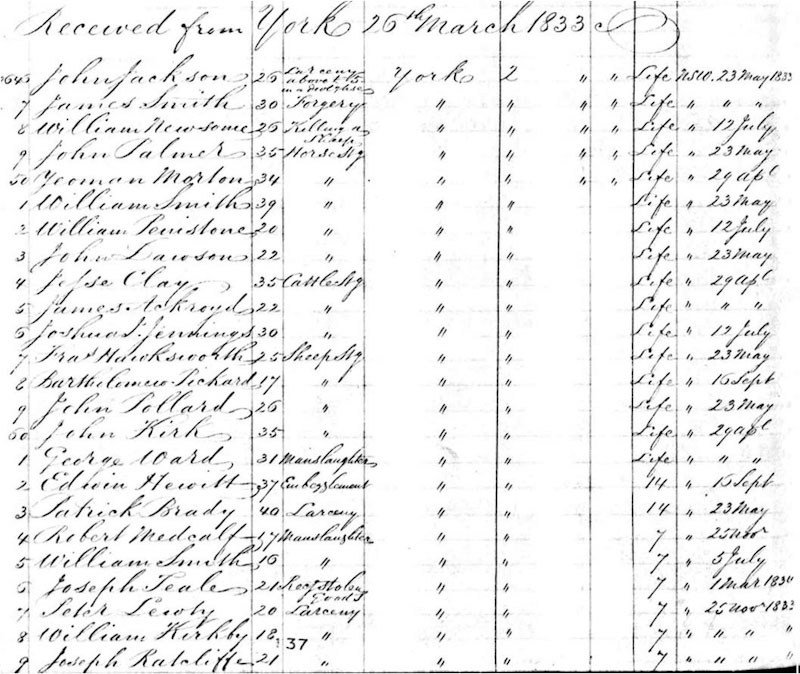

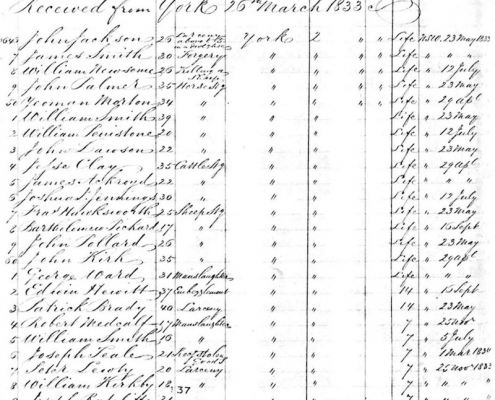

A list of those tried at the York Assizes in March 1833 and the sentences passed on them appeared in a Leeds newspaper.1

The summary of the assizes makes a distinction between those receiving sentence of death and those against whom a judgement of death was recorded. William Walker came in the latter category and none of the twenty-five prisoners in this category were executed, nearly all had their sentences commuted to life imprisonment. Of the nine prisoners who received sentence of death, three were executed and the remainder had their sentences commuted to life imprisonment.

A list of those tried at The York Assizes March 1833

A contemporary newspaper account gives more details of the incident2:

Interestingly this does not quite tie up with the court records. The newspaper account does not mention any assault on the waggoner and suggests that they had taken the box of clothes in his absence. So rather than committing a serious assault, it appears that Peter may have acted on the spur of the moment and stolen an unattended box. Whatever the truth of the case, Peter paid a severe price for his crime.

Prison Hulks were old warships that were moored up and used as floating gaols.

Peter was taken to Sheerness and held in the prison hulk Retribution from March until the following January. Prison hulks were old warships that were moored up and used as floating gaols. Rendered unnavigable by the removal of sails and rigging, the internal fixtures would have been refitted to accommodate several hundred prisoners. Retribution has been launched in 1779 as the 74 gun third rate HMS Edgar and remained in service almost to the end of the Napoleonic Wars. It was converted into a prison hulk in 1813 and renamed Retribution and was finally taken out of service and broken up in 18353.

Conditions on board were appalling, with poor standards of hygiene and few medical facilities.

A contemporary description of life aboard the Retribution gives a feel of what it must have been like:

“There were confined in this floating dungeon nearly 600 men, most of them double ironed: and the reader may conceive the horrible effects arising from the continual rattling of chains, the filth and vermin naturally produced by such a crowd of miserable inhabitants, the oaths and execrations constantly heard amongst them…”

“On arriving on board, we were all immediately stripped and washed in two large tubs of water, then, after putting on each a suit of coarse slop clothing, we were ironed and sent below; our own clothes being taken from us…”4

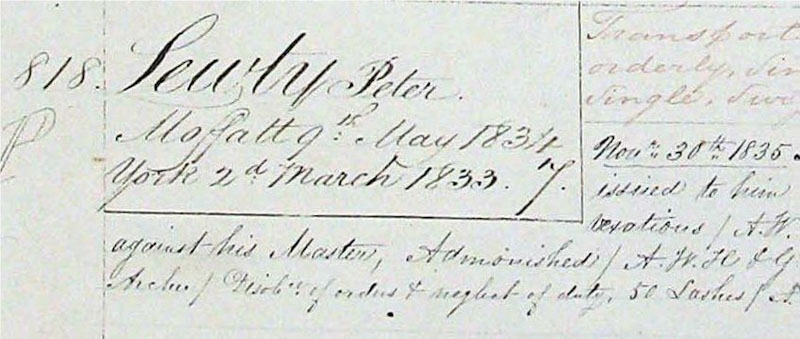

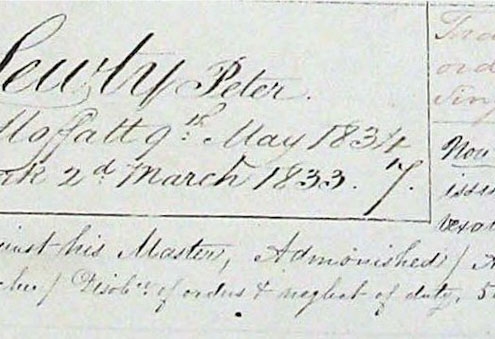

This is an extract from the prison hulk register:5

The aim of the government was that life on the hulks should be “sufficient to make it an object of terror to the evil doer”6 and they certainly seem to have succeeded in this aim. George Loveless, one of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, described his arrival on a prison hulk at Portsmouth in 1834:

When I went on board I was struck with astonishment at the sight of the place, the clanking of chains, and of so many men being stripped. When ordered to put on the hulk livery, and to attend to the smith to have fetters rivetted on my legs, for a moment I began to sink down”7

Prisoners did not spend all their time on the hulks. They were taken on shore in work gangs and made to labour in the dockyard or on other local works. They would be chained and closely supervised whilst doing this.

In 1847 a radical MP accused the superintendent of convicts of gross neglect of duty and mismanagement of the hulks which led to the appointment of a prison inspector to investigate the condition of the hulks at Woolwich. His report was damning8. He said that, even on the hospital ship, the diet caused scurvy and the oatmeal was so bad that the convicts threw it overboard; that most of the patients were infested with vermin; and that cleanliness was non-existent. Life on the hulks was described as “Hell on Earth”. The hulks were gradually phased out after this.

In January of 1834, almost a year since his trial, Peter was taken to Plymouth and transported to Van Diemens Land (now Tasmania) on the transport ship Moffat which sailed on 29 January 1834 and arrived in Tasmania on 9 May. One hundred days was quite a fast voyage for the time. The ship carried 400 male convicts, 393 of whom reached Tasmania.

Conditions on the Moffat would have been harsh and spartan, but not as bad as they were on some of the earlier convict transport ships.

Convict ships were privately owned converted merchant ships which were chartered by the Government. From about 1815 greater care was taken of the health of the convicts and the death rate fell considerably; it has been claimed that many convicts arrived in better health than when they left England. Each ship had a naval surgeon who was responsible for the health of the convicts; as well as being medical officer they also acted as government agents “with full power to exercise their Judgement, without being liable to the Control of the Masters of the Transports”. In the years before 1815 the death rate averaged 1 in 31; after 1815 it dropped to 1 in 122, and seldom more that 1 in 100.9 So the seven deaths on board the Moffat were well above the average.

However, even if conditions were improved it must still have been a long and tedious voyage. The convicts lived in crowded quarters and security was necessarily tight.

Peter’s conduct record during his imprisonment and transport10 is somewhat contradictory:

Gaol report: Very bad

Hulk report: Orderly

Surgeon’s report: Behaved well

The surgeon’s report would be from the surgeon on the transport ship. The variations suggest that he was troublesome at first, but as his imprisonment continued became resigned to his lot.

Chained and boarding for transportation

It was not inevitable that sentences would be carried out as given; there was room for convicted criminals, or their family and friends, to make a petition when they wanted to revoke or reduce the sentence. Occasionally, the governors of convict prisons recommended prisoners for early release for good behaviour.

In Peter’s case the petition came from a number of local people11. It was not approved.

To His most gracious Majesty William the Fourth King of England

Petition

To his most gracious Majisty King William the fourth

The humble petition of the undersigned, a few of your gracious Majesty’s loyal subjects, being respectable Inhabitants of the Parish of Guiseley and County of York humbly Petition your gracious Majisty on behalf of an unfortunate young man Peter Leuty Convicted and Sentenced to Transportation for several years at last York Assizes.

He has lived amongst us upwards of Nineteen Years, and borne a good character for industry and probity, until a short time previous to the committing of the unfortunate crime, for which he was justly sentenced to Transportation, when he became acquainted with a bad character who persuaded him to assist in stealing a box from a Wagon for which he is justly punished.

It appears he is very sorry for his former conduct and folly in the above crime, and his Parents, who have lived in this county for many years, in credit and respectability, as Labouring people, are inconsolable.

They have no wish for the time of his Transportation to be shortened, inless his future conduct should deserve such clemency, but they deprecate his being sent over Sea, as he whould never have the benefit of their precepts and example, to regulate his future conduct not have the opportunity of shewing that contrition, to his country and family he might otherwise do.

We therefore humbly Petition your gracious Majisty on the above grounds, and as it is the first time he has been convicted of any Offence. May it please your Majisty to extend your Royal clemency, and not suffer him to be sent over sea.

And your petitioners as in duty bound will ever pray for your Long and happy Reign.

John Parkinson Grocer William Rawlinson Tailor

Josh Dawson Shop Keeper George Gardiner Surgeon

Isaac Spencer Carpenter John Parkinson Shop Keeper

John Holdswoarth Farmer Wm Lumley Teacher

- Leeds Mercury. 16th March 1833

- Leeds Mercury 9th March 1833

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_British_prison_hulks

- Vaux, James Hardy, Memoirs of James Hardy Vaux, 1819

- National Archives H09/7

- Williams, J. Richard, Sentenced to Hell, 2011

7. Loveless, George, The Victims of Whiggery, 1838

8. Report on Inquiry into the Hulks at Woolwich, Parliamentary Papers, xiviii p.831

9. Hughes, Robert, The Fatal Shore, London 1987

10. Tasmania State Archives – database no.42642

11. National Archives: H017/129-ZR43

Chapter 3. Van Diemen’s Land

Van Diemen’s Land was a relatively new colony when Peter arrived, but had been developing rapidly. The first European settlement was founded at Hobart in 1803 followed by Launceston on the north coast in 1806. Initially it was intended as a place to take some of the most disruptive convicts from Sydney in order to improve public order in Sydney and make it more attractive to free settlers. So it started as a convict colony with some of the worst prisoners and a heavy guard of soldiers. The first emigrant ship with free settlers arrived in 1816 and the first convicts transported directly from England arrived in the following year. By 1834, when Peter arrived, the colony was well established.

It was the penal colony with the worst reputation for severity. Each convict was closely questioned on arrival and detailed records were kept of their past and their behaviour in the colony. James Backhouse, a Quaker missionary, reported that the governor would often meet new prisoners when they arrived and warn them as to their conduct:

“He alluded to the degraded state into which they had brought themselves by their crimes; this he justlly compared to a state of slavery… [He told them] that their conduct would be narrowly watched, and if it should be bad, they would be severely punished, put to work on a chain-gang, or sent to a penal settlement, where they would be under very severe discipline; or their career might be terminated on the scaffold. That, on the contrary, if they behaved well, they would in the course of proper time, be indulged with a ticket-of-leave;… that if they should still persevere in doing well, they would then become eligible for a conditional pardon, which would give them the liberty of the colony: and that a further continuance in good conduct, would open the way for a free pardon, which would liberate [them] to return to their native land”.1

Records held in the Tasmanian Archives give a physical description of Peter on his arrival2:

TRADE: Farmer’s Labourer

NATIVE PLACE: Rhoden (sic), nr Leeds

HEIGHT (without shoes): 5’ 2”

AGE: 21

COMPLEXION: Fair

HEAD: Small

HAIR: Light brown

WHISKERS: None

VISAGE: Oval

FOREHEAD: Medium height

EYEBROWS: Brown

EYES: Grey

NOSE: Long

MOUTH: Wide

CHIN: Medium size

REMARKS: Woman P.L.A.

2 sprigs right arm

Rose above elbow left arm

I assume the remarks relate to tattoos, presumably acquired on the voyage.

The system in operation when Peter arrived involved seven levels of punishment between freedom at one extreme and the scaffold at the other3:

1 holding a ticket-of-leave

2 assignment to a settler

3 labour on public works

4 labour on the roads, near civilisation, in the settled districts

5 work on a chain gang

6 banishment to an isolated penal settlement

7 penal settlement labour in chains

Peter seems to have fallen into the second category and was allocated to a landowner named Archer.

The record of his imprisonment4 suggests that there was not a very good relationship between Peter and Mr Archer:

30 November 1835 – Appeared to complain of his master for not having his weekly ration issued to him at the proper time on Saturday evening – complaint dismissed being frivolous & vexatious

Same date – Absent without leave & making complaint against his master – Admonished

14 January 1837 – Idleness under pretence of illness – 25 lashes

1 February 1837 – Disobedience of orders & neglect of duty – 50 lashes

Peter was freed in 1840 on completion of his sentence. A notice appeared in the local newspaper listing the convicts who had completed their sentences and inviting them to apply for certificates of their freedom.5

Convicts were free to return to England at the end of their sentence, but they were not given any assistance to do so and few could afford the cost of passage.

So, Peter had no choice but to remain in Tasmania.

- Backhouse, James, A Narrative of a Visit to the Australian Colonies, 1843

- Tasmania State Archives – CON18/15

- Hughes, Robert, The Fatal Shore, London, 1986

- Tasmania State Archives – CON31/28 p145

- Hobart Town Crier and Van Diemen’s Land Gazette, 6th March 1840

Chapter 4. Marriage

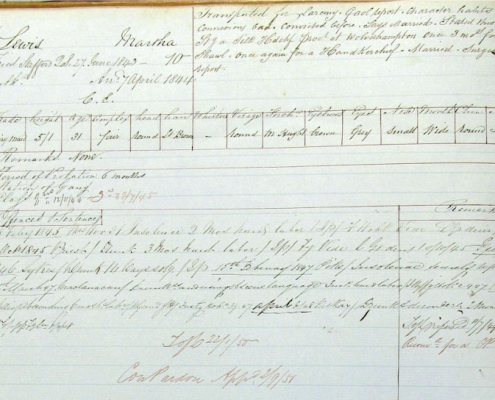

Peter married Martha Lewis in Morven in 1848.

According to the Tasmanian convict records1 Martha was born in Flintshire in 1814 and at some point, moved to Staffordshire where she worked as a dairy maid. She was convicted of larceny at the Stafford Quarter Sessions on 27 June 1843 and transported for seven years.

The gaol report stated that her “character habits and connexions” were bad and that she had been convicted before (stealing a silk handkerchief, stealing a shawl and once again for stealing a handkerchief). It also says that she was married.

She was transported on the ship Emma Eugenia which sailed from London on 30 November 1843 with 170 female convicts on board and arrived in Tasmania on 2 April 18442; a voyage of 124 days. A copy of the surgeon’s log for the voyage is included as appendix A.

By the time Martha arrived in Tasmania a probation system had been introduced whereby convicts spent an initial period in work gangs on public works (in Martha’s case this was six months) and then were freed to work for wages within a set district.3

Her record in Tasmania was not very good. In the three and a half years between the beginning of 1845 and the middle of 1848 she had received two sentences of two months hard labour, two sentences of three months hard labour, fourteen days solitary confinement and a severe reprimand; these were mainly for either insolence or being drunk and disorderly. She had also received six months hard labour for absconding.

Because Martha had not completed her sentence she had to ask permission to marry. In February and again in June 1848 she applied for permission to marry George Webby (a former convict who had completed his sentence); these request were both refused4. However, when in October of the same year she applied for permission to marry Peter Luty the request was approved5 and they married on 13 November 1848.

Convict Record of Martha Lewis. Morven 1848.

- Tasmania State Archives – Conduct Register of Female Convicts arriving in the period of the Probation System – CON41/1/1-Z2590

- Tasmania State Archives – database no. 42566

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convicts_in_Australia

- Tasmania State Archives – CONS 52/1/2 pages 349 & 402

- Tasmania State Archives – CONS 52/1/3 page 273

Chapter 5. His Last Journey

In 1852 Peter travelled to Melbourne. The passenger list of the ship on which he travelled gives the following information1:

Family Name: Lewly (sic)

Given Name: Peter

Rank: Steerage

Ship of Departure: Shamrock

Date of Departure: 18 Mar 1852

Port of Departure: Launceston

Where Bound: Melbourne

Ship to Colony: Moffat

Status: Free by servitude

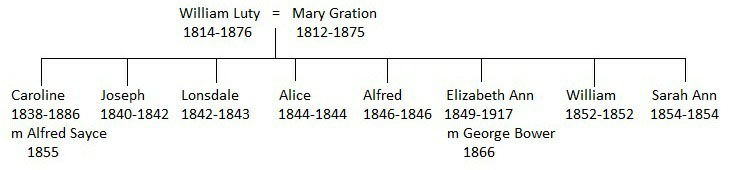

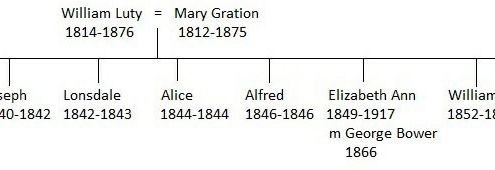

I think he must have travelled to visit his brother William.

William Luty & Mary Gration’s Children

William was two years younger than Peter. He married Mary Gration in Bradford in 1836 and they lived in Shipley where William worked as a tailor.

William and Mary emigrated to Adelaide with their eleven year old daughter Caroline and their six week old daughter Elizabeth (the only two of their six children who had survived) in 1849, sailing from England ion 22 September and arriving at Adelaide on 26 December.

They remained in Adelaide for about a year and then moved to Collingwood, a suburb of Melbourne. They had two more children in Melbourne, both of whom died shortly after birth. Both Adelaide and Melbourne were recently established having been founded in the mid 1830s. Melbourne developed rapidly after gold was discovered in late 1851 (75,000 people arrived in the colony during 1852), but conditions must have been quite spartan. The river Yarra was the main water supply and became quite polluted, leading to outbreaks of typhoid in the 1850s.2

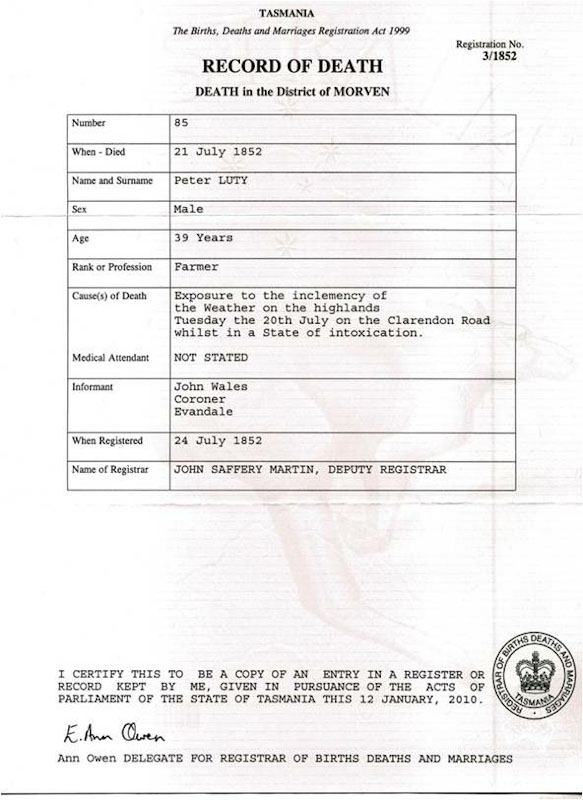

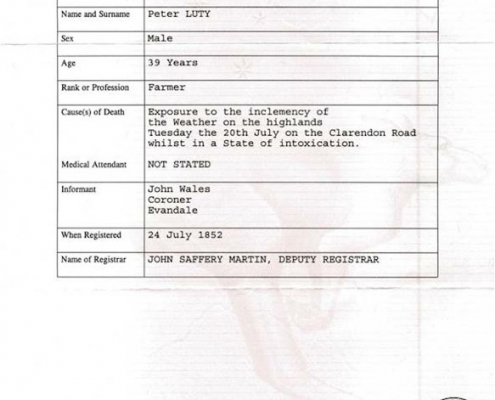

I have not found a record of Peter’s return to Tasmania, but he must have done as he died there later that year3.

At the time of his death Peter was living in Evandale in the north east part of the island, about 20 kilometres south of Launceston. He was making a living as a farmer.

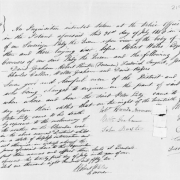

His body was found south of Evandale on the road to Clarendeon on 21 July 1852. Later that day an inquest was held into his death and it was found that “on the night of the twentieth of July the said Peter Luty came to his death by exposure whilst in a state of helpless intoxication”.4

Inquest Report. Death by exposure whilst in a state of helpless intoxication.4

After Peter’s death Martha married Michael Boyce on 4 October of the same year. Michael died in Launceston 19 January 1889 and Martha on 7 July 1890 at the age of 78.

- Tasmania State Archives – POL220/1 p615

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Melbourne

- Death Certificate – Tasmania, Morven District – reg. No. 3/1852

- Tasmania State Archives – SC195-1-32 Inquest 2760

Appendix A. Emma Eugenia Surgeon’s Log.

At daylight on the 13th & 14th November one hundred and seventy female convicts were embarked at Woolwich from Millbank Prison.

With the exception of seven or eight who had been recently ill of Diarrhoea their general health was good. a reference to the Sick Book will show that the health of (nearly) all continued good from the day of embarkation in England to debarkation in Van Diemen’s Land, a space of upward of five months, or one hundred and fifty three days.

Three only of the nineteen cases were accompanied by damage, Sophia Jacobs, Jane Tate & Hanna Harley. Diarrhoea was the prevailing complaint throughout. Scarcely a day passed without a case, but when instantly attended to, the disease was easily and speedily removed without confinement to bed, or admission to the hospital. When the complaint made its appearances the usual practice was the exhibition of half an ounce of Sulphate of Magnesium in two doses, an ounce of castor oil in a similar manner, followed at bed time by twenty grains of Species Ins. Confectione Opii, as a dose of chalk mixture with tincture of Kina &Opium.

A month before our arrival at Hobart Town, all the aperients as well as the astringent Medicines were expended. In addition to the eight ounces of tincture of opium allowed, three times eight ounces were made on board and expended in the treatment of loosengs. In the treatment of Diarrhoea Species pro Confectione Opii was found an excellent remedy, the short time it lasted, and I am inclined to think it will always prove most valuable in a Female Convict Ship. Three times the usual allowance, in this instance, would have been of the greatest service. From first to last, there was nothing bearing the slightest resemblance to Scurvy.

The sick were visited twice a day regularly, and often more frequently. During a Gale the Prison & the Hospital inspected four or five times a day. When the weather permitted the usual routine on board was as follows.

The Prisoners were allowed to be on deck from Sunrise to Sundown.

7 a.m. Windsails up, Scuttles, Ventilations, & Hospital Stern Ports open. Beds /32/ & Bedding of four Messes in succession were aired daily on the Poop.

8 a.m. Breakfast.

8.30 a.m. Commenced cleaning lower deck. The space opposite each Mess was given in charge of and daily cleaned by the two Mess women, in the first place sweeping clean, and then by the application of coarse woollen cloths dipped in water & thoroughly wrung. Scrapers occasionally.

Especial care was always taken that not a superfluous drop of water was used. Except during a Gale, the Prison was as clean, dry, and well-aired as any Prison on Shore. Vinegar, Chloride of Lime, or Hanging Stones were never required. The abomination of Dry Holy Stoning was carefully avoided, and ever will be, until I can perceive the difference between the atmosphere of a Dry Holy Stoned Ship, and a Sheffield Dry Grinders Workshop.

10 a.m. Visited Sick and afterwards carefully inspected Hospital and Prison, daily turning up the whole of the Bottom Boards.

4 p.m. Visited Sick & inspected Prison.

The leading features of the system pursued throughout were, unremitting attention when Sick, constant employment when well, & unceasing surveillance. When the Vessel arrived at Hobart Town, there were three cases in the Hospital, Chronic Gastritis, Chronic Rheumatism & Sanguineous Diarrhoea. Sophia Jacobs continued in a state of distressing debility, accompanied by low muttering delirium, upwards of three weeks. The discharge from the two large abscesses on each side of the spine in no way retarded recovery. Jane Tate the Principal Hospital Nurse appeared to owe her attack of fever to constant Attendance on Sophie Jacobs. Hannah Harley had a protracted attack of Diarrhoea in Shrewsbury Jail, besides one or two attacks in Millbank Prison. M A McDonald, this case is marked Amnemoxii because the symptoms appeared to indicate this disease, but her speedy and complete recovery renders this designation more than doubtful. Ellen Lane. along with Diarrhoea, had Hydrops Genus, and here as well as in the case of Alice Moore, the latter disease readily yielded to the application of two blisters. Jane Grady. This case is marked Dyspepsia in the absence of a more appropriate designation. The patient had had a very irregular life for several years and was nineteen times in jail before Conviction. Her present illness appeared to be the consequence of her jumping overboard half way between the Cape & Hobart Town. She had handcuffs on at the time as a punishment for striking & wounding the Chief Officer. About fifteen minutes afterwards I caught her by the hair about half arm’s length under water. Of the four cases sent to the Hospital Chronic Gastritis, /White/ Sanguineous Diarrhoea/Harley were discharged cured five or six weeks afterwards. Chronic Rheumatism /Hunt at the expiration of four months remains Diarrhoea /Hinton/ after one or two relapses died in Hospital.

John Wilson MD. Surgeon

http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~austas/emmasurg.htm