The Ramblings of My Mind

Eric Frederick Burnett 7th April 1920 – 8th May 2002

These are the memories of my father, Eric Burnett. He committed these memories to paper at my request, some years before he passed on 8th May 2002. He also recorded them for me because I had such difficulty in reading his handwriting. I had them professionally transcribed some years ago. The audio file is available below. Unfortunately, because he recorded them on cassette tape, the second tape became entangled and snapped. I have therefore finished relating the memories on his behalf.

The Ramblings of My Mind

Foreword

These writings were conceived in my mind some years ago and were born today. It has been said many times that there is at least one book in each of us. I don’t know about that and can speak only for myself. If a host of written words, transferred unaided from the head to paper, can be described as a book, then the following narrative is my book and I have proved a point. But I do not deceive myself: books are written for eventual publication and I cannot believe that what I have to say could prove remotely interesting to anyone, save possibly my wife and children and only then because they are who they are, and by virtue of that fact they are part of me and automatically part of it. Others close to me could display some interest if I were to invite their attention, but my efforts are purely selfish and are designed only to satisfy a longstanding desire to commit myself to paper and see what happens.

In view of this, the subject matter is unimportant but it will give me pleasure for it is the story of my life. It will have no beginning and no end and will relate to random memories. It will not be a chronological sequence because I have been methodical all my life and orderliness is only another word for dullness and mediocrity. In short it will be a hotchpotch of thoughts.

I only wish that I could transfer words to paper by some magical method as they flood into my head, for if this were possible, I would surely be recognised as the most prolific writer of all time. My job is ideally suitable, for the hours I spend behind the wheel of a motor car can only be used in thought and meditation but followed immediately by frustration, for surely the problems I solve and the theses I propound are lost to me before the end of my journey.

Only the memories are sweet and satisfying but they are of no significance except to me.

But enough. I’m reminded of my daughter’s oft-spoken plea, ‘Dad, why do you use so many words to answer me?’ To her, my son and my wife I say, ‘Bear with me. I am what I am but without you I am nothing’.

Many years have passed since I sat down to begin this narrative and they’re wasted years, but I will try and bridge the gap because you, Paul, have begged me so often to do it and if you think I’ve got something to offer then I owe it to you and to Michelle, to my dear wife Joyce, and to our grandchildren, because I love you all so much.

It is summertime and I am walking towards the river, alternately pushing my tiny daughter in front of me and pulling her behind me in her pushchair. She screams with delight and I’m content, for we have escaped from a world of greyness into sunshine and happiness. Paul is at school and I have escaped from my mediocre job of off-licence manager during the afternoon and non-opening times.

The seed of discontent with my new occupation was planted in my brain only a short time after we sold our first real house and where we were very happy, to commence anew. The seed exploded into bud on the Christmas Eve of our second Christmas some fifteen months after we arrived.

My wife and I were working under great pressure serving the revellers. The children were in the sitting room, which was situated between the cellar and the shop. I had to make constant trips to the nether regions for crates of ale and each time I passed through the sitting room our baby daughter, who was sat in a chair sucking a blanket, her comforter, reached out to me, saying one word: Daddy. And I literally had to shake her clutching hand off. I told Joyce the next day that we were getting out and a few weeks later I sent my resignation into the brewery.

Had I known then what our son told us many years later my decision would have come even earlier. He was only about eight at the time and apparently going to bed was a frightening experience of some magnitude.

The house part itself was very big and very old. We were also worried each day when he went out to play after school, because the River Mersey flowed by only some 50 or 60 yards away and it contained a weir and even now, I shudder when I see one.

Anyway, I knew I was capable of a better and more satisfying occupation, and so when the three months’ notice expired, we used our returned deposit and moved to a new house in a much more salubrious area and we were all happy. We had only one problem. We had a mortgage, but I had no job.

I started work almost immediately after I was 15, armed with a much prized and rather beautiful scroll which declared my achievement in passing in eight subjects from St. Margaret’s Central School, Whalley Range. I was made school captain shortly before I left and had represented the school in the Shield Cup and senior teams as outside left in the football team. We didn’t call it soccer then.

(Paul Burnett) Above is the first house that my dad refers to. I have very fond memories of this house as I spent my young years here playing with my pals Bryn and Chris who lived just a few doors down. I recall my bedroom was at the back, no such thing as central heating, so in the winter I could physically scrape the ice of the inside of my window with my finger nails. Going to bed however, was a pleasant experience because my dad placed a paraffin heater on the landing outside my bedroom door. The heater was very efficient and warmed all of the upstairs rooms including my bedroom. I can visualise it now and my memory also brings back the comforting warm smell of the burning paraffin.

We were extremely poor, as were the majority of people, and being one of six children money came first with ambition a long way behind. My mother was a caring woman who seemed to never stop working. She was old before her time and to me had never seemed young. My father was a traveller. Again, it was a description used for today’s sales representative. He was in the coal business and in keeping with his trade and occupation spent some time, consuming halves of bitter. Unfortunately, he kept company, in the main, with his boss, who was somewhat better placed financially, and my mother habitually waited anxiously each Friday night for Fred to arrive home with her housekeeping.

It was rather traumatic for me and no doubt for my brothers and sister because we knew that sharp words would ensue. My mother’s problem was that she lived from week to week and most certainly could not venture out for the late evening shopping until her purse contained

the money to pay, and the poorer people shopped late on Friday because the shopkeepers wanted to clear their shelves ready for Saturday. There were no supermarkets and no deep freezers.

My father wasn’t cruel in a physical way and I never saw him strike my mother or us for that matter, but like most men of that period he was the master of the house and my mother was there to fetch and carry and most of all worry. However, shortly before I left school, he had a dispute with the employer mentioned over some commission. He said it was owing. In the heat of the moment, it seems, he told his namesake, Fred – Fred Price actually – to stick his job where monkeys stuck their nuts! Despite repeated overtures from his boss to forgive and forget and return to his job my father remained adamant and my mother wept. She now had eight mouths to feed on the wages of two elder brothers and a sister.

In the mid-Thirties times were hard and jobs few and far between. To give an example: I believe my dad earned £4 a week on commission and he was quite well paid. His employer, my mother told me, in conclusion took on two men to replace my father and paid them £2 each. For whatever faults he had he was intelligent but misguided, and so, after a few weeks, and very sore hands, I applied for a job as a warehouse boy in a wholesale wallpaper warehouse for ten shillings a week. Now I was really living and working in the city.

The business was run by two brothers, one in charge of the warehouse and one in charge of the office, with the help of an obliging secretary.

It was imperative that I start work and I did, chopping rope for eight shillings a week. Despite our dire straits my mother always wanted something better for us and I like to think that I inherited that desire and also some of my father’s better traits.

One of my duties was to deliver paint and wallpaper to various destinations in the city and on one occasion I had a gallon drum of paint loaded on my ironclad. This was a truck with a small steel shelf lower than the handles and just above the wheels, which were steel and made an awful noise as it was trundled along the pavements and cobbled roads. When crossing the road, one had to go forward off the pavement and then in reverse to go up the opposite edging.

Unfortunately, I was crossing Deansgate, I believe, and facing Kendall’s on the other side. Now to all the city errand boys, at least those with the blood of youth coursing through their veins, these shop windows needed to be passed at a slow pace to allow time for surreptitious glancing at what were, to us, gorgeous girls dressed in the customary uniform of a severely cut black dress. As I was approaching the opposite pavement the assistants were window dressing and to my absolute amazement one of the girls bent forward a little too far and one of her breasts dropped out, which she nonchalantly popped back, but the damage was done. The wheels of my truck hit the edging and the drum of paint popped out and burst with an avalanche of white paint spreading like lava across the pavement.

My last recollection was seeing the girls shrieking with laughter as I fled in panic to confront my employer. My explanation must have been pretty good, because I received a severe reprimand and warned that wanton destruction of company assets would not be tolerated again.

However, my employment with the firm was shortly to be terminated in an abrupt and, to me, tragic manner. I had been dispatched by the lady secretary on an errand and given a ten-shilling note to pay. Carefully avoiding Kendall’s I made my way, but on arrival found, to my consternation, that the ten bob note was no longer accompanying me and I returned, dismayed and crestfallen, to report its demise to the secretary, who flew into a rage and accused me of stealing it. She said I would be reported in the morning to Mr. Allen and to prepare myself for the worst, the said gentleman being out at the time.

I went home and told my mother and father. My mother cried and my father raged, not at me but at the woman who’d dared to accuse a son of his of theft, and he said he would accompany me the following morning to my place of work. This cheered me up considerably. He could frighten me just by looks so I feared the worst for her and her paramour, who always looked too well fed and self-satisfied. My expectations were fully justified. My father marched in and confronted them both and demanded in stentorian voice an apology ‘or else’.

The woman wept copious tears and Mr. Allen stammered that a mistake was made, and the matter would be forgotten. However, this was not good enough for Dad, who replied that he would not have his son work for such low-principled people and stalked off triumphant with me trailing behind. This left me once more scanning the vacancy columns for job vacancies.

The Manchester Evening News came up with an advertisement, placed by a leading shirt and pyjama manufacturer trading under the name of ‘Mentor’, or W.M. Miller & Company. I applied successfully and started for a weekly wage of twelve and sixpence.

It was a somewhat boring and humdrum existence, only relieved from time to time by certain situations, sometimes amusing and often not. The owner, a Mr. Cluney Saint Clair Miller (it suited him admirably, but I believe the capital ‘C’ in his Christian name had either been added as an afterthought, or it was a mistake; I’m not sure which). He lived in a large, extensively grounded property in Alderley.

He was an arrogant pig who never ceased to display his power, particularly over his departmental managers. My particular manager suffered more than most. He was a gentle person whose voice I never heard raised in anger and we, his staff, often gave him reason to. We were two floors up from the general offices and the directors of boards. When Mr. Miller required the presence of Mr. Arnold, he would open his office door and shout, in stentorian tones, ‘Arnie! You long streak of wet piss! Get down here!’ To illustrate the man even further, another of his pleasant little ways to display his superiority was manifested when he performed his floor walks.

Smoking was strictly not allowed of course except by him, and he would throw his tab end on the floor, kick it to the nearest warehouse man, and snarl, ‘Pick that up!’ Yet another of his endearing habits would be to sit on the bench which ran the length of the room, raise himself up, fart loudly, then look at whoever he was talking to. Had it been for applause he might well have earned some admiration, but it was merely another display of superiority over his downtrodden workers.

We had a very longstanding employee called Mr. Fox, who also suffered acutely from wind, but not because of rich food. He had a complaint which required him to suck sulphur tablets on a more or less continuous basis and this resulted in the most disgusting smell that one could imagine. It was more insidious because it was soundless. He worked in the basement, and usually on his own. On this particular occasion he was suffering more acutely than usual, and he had more visitors than usual. It was reported to the Chief Cashier that there was an obscene smell in the basement, and off he went to investigate. Mr. Fox said his sense of smell wasn’t very good and thought it might be dead rats under the floorboards, probably from the nearby canal. Within the hour council workmen were taking up the floor and Mr. Fox had to keep retiring behind the racks until his bouts of laughter subsided.

Life continued uneventfully for us in the warehouse and even more boringly for the young ones. My father left us and went to London to seek work, he said, and to trace his forebears. This became an obsession, because I think he believed that he had been defrauded of some money. My mother struggled on and we moved to a better house in a more salubrious area, Old Trafford no less, which at that time was quite considerably more up-market than Moss Side. There were now four of us working and at least my mother didn’t have to wait hopefully for some money, because unlike my father we paid our dues to the woman we all loved, despite her lack of emotion, but we knew beyond a shadow of doubt that she loved us and the clouds of war gathered in Europe. It was early 1939.

I had now become very restless and bored with my job. I had recently been promoted to a more important position and was earning the princely sum of eighteen shillings per week. As was customary in most working-class families, I had reached an age where I could negotiate with my mother a new deal, namely keeping myself. This simply meant that I gave her less money, but I kept myself. For example, clothes, and items which she normally provided. I don’t remember the figure, but I suppose I would have, say, seven and sixpence per week and she would have the balance for food and rent, etcetera, etcetera. She would still pay my fares to work, but this was only coppers. Tram cars were on the way out and buses coming in. My friend Derek, who I met soon after leaving school, had terminated his short career as a butcher’s

assistant to join the Merchant Navy some eighteen months previously, and I envied him. But my loyalty to my mother, particularly in the circumstances, held me back because I knew that at the end of one trip one did not necessarily qualify for the next, and even so, one was only paid for the duration of the voyage. His family we were also working class but were better placed because he had a stepfather who earned and two working sisters. I suppose I wished that war would overtake us, and for more than one reason. It could mean I would have to leave my despised and mundane job of work without a conscience and not needing excuses.

My brain raced ahead and as we drew closer, I became, like most of my age group, inflamed with the thought of leaving home for foreign lands to fight for King and country.

When I look back in retrospect I realise how lucky I have been and how very foolishly one thinks at such an age. And yet I do not regret the experience, but only the wasted years in other ways.

As that fateful day in September approached, I decided that my days with the ‘Mentor’ would be terminated and voluntarily, and that I would join the navy and be like my friend – that I would be active. Oh, how the picture overwhelmed me. I was besotted. The thought never even occurred to me that I would be welcomed with nothing less than open arms by His Majesty’s Royal Navy. I was summoned shortly after my application to a naval medical centre. I didn’t doubt for a moment that this was the first step to my sea-going exploits to foreign parts and maybe even confronting the Germans.

Alas it was not to be. I was completely devastated when I appeared before the Chief Examiner after getting dressed. He was very sympathetic when he said, ‘I’m sorry son, you’re physically A1, but because of defective vision I have to grade you B3. I’m afraid it’s the Army for you, lad’. The price was even harder to swallow when, later in the year, my older brother received his conscription papers. He asked for the Navy and was accepted. The qualifying minimum age for conscription was twenty, and so Norman went first. Some knowing person told me that minesweepers operating in coastal waters did not bar people who wore spectacles and off I went with fresh heart; perhaps not as enthusiastically, but I thought that at least I would be at sea, and it had to be exciting.

My hopes were dashed once again, and I returned home in despair. About that time my friend Derek returned from his latest voyage and regaled me with tales of his exploits. About the same time one of my friends at work had been accepted into the Merchant Navy and I imagined I would be left with the old man. Derek and I did the rounds as we always did. We were bosom pals. We’d go dancing and frequented the locals as far as our funds allowed. As a matter of interest, a pint of bitter was five pennies, old money of course, and ten Players medium were sixpence.

This probably was a little understated at that time, 1939, and those were the prices some three years’ previously, but inflation was a word out of the dictionary and prices had not inflated very dramatically.

However, to continue, the conversation always came back to my predicament and Derek urged me to join him if even for the odd trip to see how I liked it and to fill in the time until I was twenty and eligible for call up. He was not completely sold on the life, but we would be together, and he might decide to join an arm of the Services.

It was early 1940. The war had been started, or I should say declared, many months ago but it appeared to be a damp squib as far as the UK was concerned. So off we went to Manchester Docks, which at that time was a thriving inland port with lots of deep-sea vessels coming down the canal. Derek had done his previous trips as deck boy, but was now offering himself as an ordinary seaman, which is the next rank up. My friend said one had to go for a medical before each voyage, but it was a mere formality. The winter of 1940 was a particularly vicious one consisting of snow and ice. We climbed the ladder and walked up the gangplank of cargo ship after cargo ship, picking our way across icy decks strewn with ropes and hoses and icicles hanging everywhere and always asking for the bosun, who is roughly the equivalent of a foreman ashore. The success rate was zero and Derek suggested we try London where there was a greater input of ocean-going vessels. And so, the die was cast. I handed in my notice at my place of work to a mixture of, ‘Good for you lad’ and ‘You’ll be sorry’.

The hardest part was to come, which was telling my mother. She accepted it as I recall without any great display of emotion, but I knew that her heart would ache for me. She often said I was the nearest approach to my father, but she also knew that I wasn’t deserting her but just saying goodbye for a while. I have never known what the reaction was from my brothers and sister. I packed a few belongings and my mother packed me some butties and off we went the following day. I promised my mother that I would find my father in Chelsea and tell him what I thought about him. Indeed, I had it in mind to go beyond words when I saw him. Oh, the folly and bravado of youth. An uncle on my mother’s side, on hearing my actions, said I should have more sense than to go mooning round the docks.

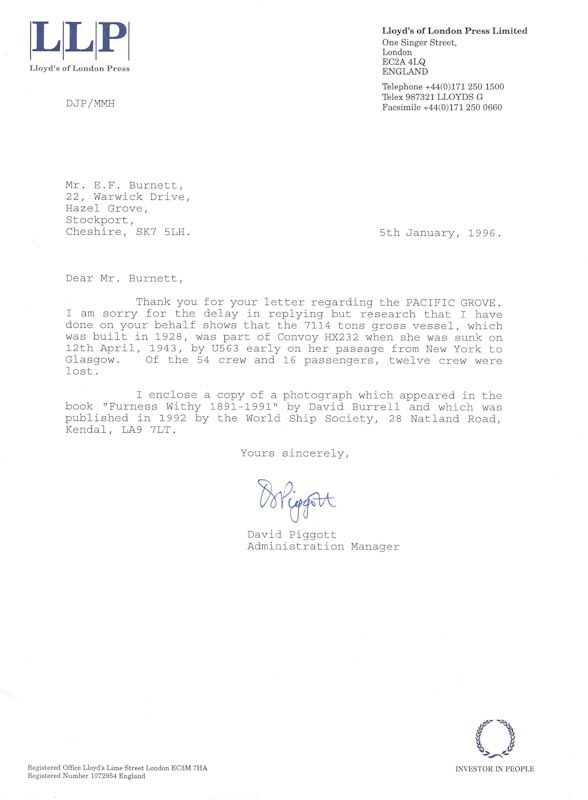

On arrival in the ‘Smoke’ we headed for the East Surrey Docks and resumed our quest, or unlucky perhaps as it turned out, because one of the first vessels we boarded was a fairly largish cargo ship belonging to the Furness Withy Line. She was, I think, about 9,000 tons and named The SS Pacific Grove.

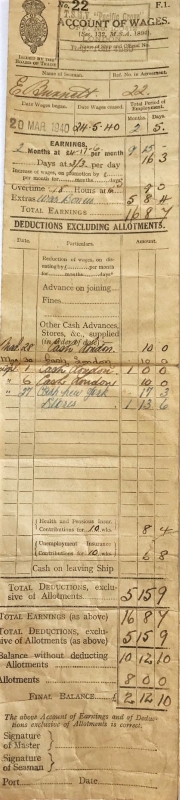

The bosun was a large, quietly spoken Swede called Larry Jason. He signed us on and instructed us to see the dock’s medical officer. At this point my friend turned to me and said, ‘Look when I’m at sea my name’s Alfie, and from now on you are Fred’. If we said, we were Eric and Derek we’ll be crucified and what’s more you’d be well advised to take your specs off and keep them off until we sign off’. At the time I thought he was exaggerating but I soon revised my thoughts. The medical proved to be the charade that Derek had predicted. The medic barely looked at us, stamped our books and we returned to the ship and to an experience that became branded on my mind like a tattoo.

The ship’s deck crew consisted of ten seamen and two deck boys, and was made up of ordinary seamen, able seamen and a coxswain and Bosun, who occupied a cabin, and of course myself and my contemporary, who, for some reason, were referred to as Peggies. I have never bothered to find out why the lower orders on a ship are nicknamed so, but I’m sure any long-serving merchant seaman of the old school would elucidate.

Our quarters were at the stern of the ship and below decks. I can only describe it as a large cabin-type room called the Foc’sle, reached by a ship’s ladder from the deck and to the best of my memory housed twelve bunks in tiers of three on two walls [tape appears to say ‘tiers of three on two rows’]. It was situated over the twin ship’s screws and was of course very noisy until one got used to it.

My friend and I, and an AB who introduced himself as Taffy Williams, arrived well in advance of the others and it was customary to select the bunk you fancied on the basis of first in, first served!! Apparently, the highest bunk was the favourite in the event of a collapse, and the one most adjacent to the door to make a quick exit should the ship be hit or fired. However, it quickly transpired that the choice was not one to be made in that orthodox manner.

The man Taffy had other ideas. He took a fancy to Alfie and me because like most ignorant, uneducated men he respected the opposite qualities in others provided they did not exercise their superiority in a disdainful way.

Taffy was a frightening character. He had few teeth, a broken nose, cauliflower ears and a well-punched face, and in the short time we knew him, before the arrival of the others, he had told us his life story and described the lady he loved but he was at a great disadvantage because she had written him several letters proclaiming her undying love but because of his illiteracy they remained unanswered and he begged our assistance and cooperation. If we would write some replies for him, he promised us eternal friendship and protection from whoever. It was seen, as things turned out, that had we not forged this friendship with him he himself would have been the main one among others who we would need protecting from!

We realised in a very short time that he was bisexual. He craved the female gender for sure and made do with an obliging or unobliging male whilst at sea.

However, to continue, the rest of the deck crew finally assembled in the Foc’sle and were about to settle after the usual chat when Taffy stood up and in a loud voice elected himself the “boss-man” and challenged anybody to disagree. There was a loud rumbling indicating some opposition. To my astonishment Taffy picked me up bodily and threw me into a top bunk, doing the same to my pal Alfie, and instructed us to stay there. He then broke off a heavy spar of wood from a bunk and set about the rest of the crew. The small space became mayhem. In a very short time, it was over, and Taffy emerged bloodied but victorious. He had established his position, and so it remained.

As the voyage progressed I realised that there was one man who Taffy never challenged: it was the coxswain and here my memory fails me because he was not part of the melee previously described, either because he had not arrived at the time or he occupied separate quarters by virtue of his position.

However, more about him later. He was a frightening person, but in a cold, calculating, ruthless way.

The next three months were to prove, arguably, the most enlightening of my life because, as I explained in that foreword, I do not want to become bogged down with a short period of my life in case it becomes tedious.

Despite the absence of the good things in life or, who knows, because of their absence, I had a happy childhood. I’d been blessed with four brothers and a sister, and apart from the petty squabbles relative to all families, I cannot recall a rift between any of us, ever, and to this day the survivors, my two younger brothers and my eldest brother, remain as close as ever.

Indeed, since we wed, my younger brothers and I have been friends in the true sense of the word in that we have always socialised and, thankfully, our wives and children have followed the pattern. We have probably holidayed together, more than separately, particularly when our children were young, and if I wanted to pad this autobiography out I could not find a better medium than our holiday experiences, particularly when the children were young and our funds were limited, but the enjoyment certainly wasn’t.

(Paul Burnett) The SS Pacific Grove was part of convoy HX-232 en-route from New York to Glasgow. On 12th April 1943, south east of Cape Farewell, she was torpedoed by U-563, captained by Gotz von Hartmann. Out of the crew of 54 plus 16 passengers, 12 crew were lost.

My Sister & Brothers

In order of seniority, Vera was the eldest followed by Roy, Norman, Eric, Donald and Arthur.

Talking of holidays, I recall a very memorable one I spent with my friend, Derek, soon after I left school. In those days, a new bike was quite unheard of, but most lads possessed one – a bike, I mean; not a new one. They were all boneshakers and made from parts from other cycles. I say this to give the reader some idea of the enormity of what we proposed to do, and yet, to us, at that time, it was nothing out of the ordinary.

We decided to go for a week’s camping holiday in North Wales and chose an area near Abergele, the exact venue being Rhuddlan Castle. We packed our haversacks, tent, and all the necessary paraphernalia, not forgetting the most valuable puncture outfits, and set forth on our seventy-mile journey.

I cannot recall now how long it took us but I’m sure we did it by the evening. The site we chose was adjacent to the castle and next to a raised mound known, I think, as ‘Bonk Hill’. This could be verified. I believe it is well known historically because I understand it is the site of a bloody battle fought long ago and we were told that the dead warriors manifest themselves periodically. Derek and I thought it was great, but we were to revise our thinking when dark fell. It proved to be a very eerie spot, and we were entirely on our own.

The nightmare really started when we pitched camp because in our ignorance, we decided to dig out a bit of earth where our shoulder and hip would rest.

Shortly after we settled down it began to rain heavily. The water flowed beneath our groundsheet, filled the holes, and we were literally awash. There was little we could do until daylight and it proved to be a very long night. To cut a long story short the holiday proved to be a disaster. Two or three days later Derek was stricken by severe sunstroke. The weather became glorious and hot but my friend, being very light skinned, reacted dramatically and became rather ill and somewhat incapacitated. I was to regret my lack of sympathy, thinking he was putting it on a bit. I had to take him and his bike to the station and put them both in the luggage van of the train bound for Manchester. The holiday was ruined, and I decided to pack up my things the next day and make my lonely way home.

Shortly after arriving I went to his home to see him and was told that he was in hospital where he had been taken from the train. Fortunately, he soon recovered, and we put the episode behind us and put it down to experience.

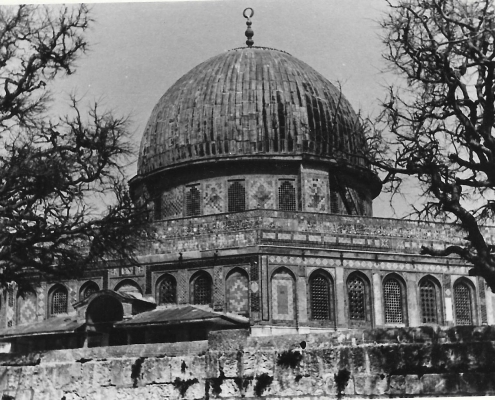

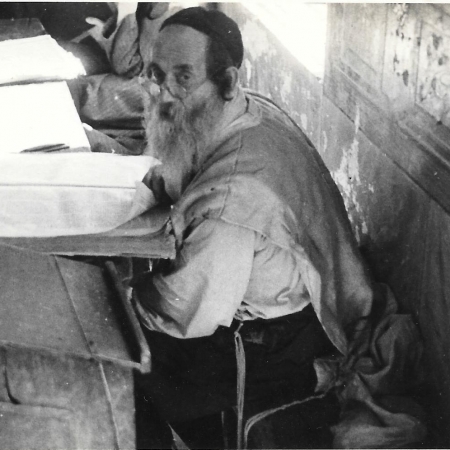

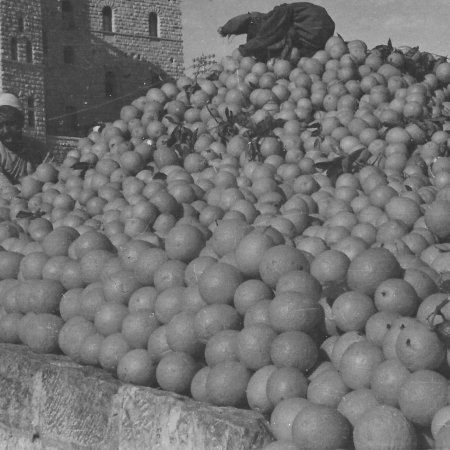

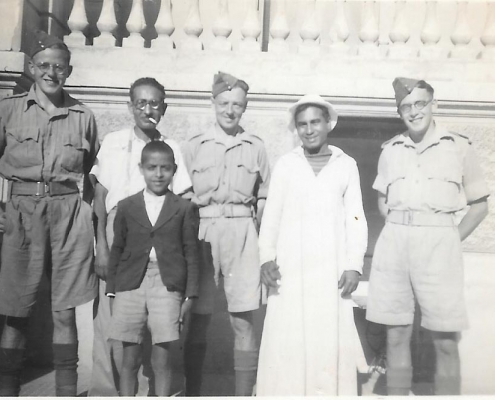

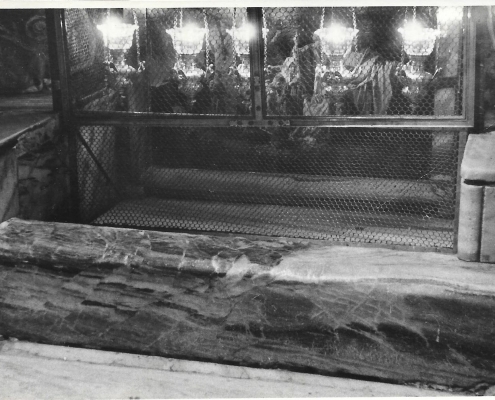

Again, on the subject of holidays the most unusual one that I have taken came in the form of a leave when I was serving in Palestine, which is now Israel of course. Those who wished to go were given permission to spend their leave on a Kibbutz. These were Jewish settlements, many of which were springing up away from the towns and were established on a cooperative basis. They were entirely self-contained and everybody within the settlement were allocated jobs and duties and nobody was paid. But if they chose to take a holiday in one of the towns they were supplied with the funds. One of the most striking features of the place that we visited was the health and vitality of everybody. Most of the young girls in there, in their very early teens, worked in the fields and orchards and resembled Amazons! I imagine they would go to seed at a very early age! The ‘Kibbutz’ was governed by a Committee with a headman and elder statesman in control. Meals were taken communally in a large hut and we of course ate with them and were given the run of the place and encouraged to participate, in the hope that we would go away and spread the word because it was obviously a form of propaganda in preparation for the independence of the Jewish State which of course was to follow in three or four years time shortly after my return home in 1946.

It occurred to me at the time that these settlements were practicing what I imagine as pure communism, but I am certain that if I had voiced this view they would have been horrified! On our arrival – hot and very dusty – we were invited to take a shower. We were basking under the cool water and chatting to each other when two young nubile females came in and began to clean the floor on their hands and knees and looking up at us and trying to converse. We of course were panicking and attempting to cover our bits and pieces. We only realised later that this was par for the course because they were not in the least inhibited. Free love seemed to be practiced but only with a chosen partner, and if the couple wished to marry, the ceremony was performed by a visiting Rabbi. The children spent the daytime in a nursery, or crèche, and were cared for by the elder women and collected by the parents when their day’s work was over. It was a very impressionable week and extremely restful and I wonder all these years later how the idea progressed and whether if some of those people of my age and younger were to read these words would perhaps correct any inaccuracies and give a more factual account than my brief efforts.

During my tour of duty in Palestine I was to experience another episode in my life but a much more unpleasant and mentally painful one. This is described in the attached letter I addressed to a newspaper for publication, but for some reason decided not to send. Whether I would have participated, had I been invited, will always remain a subject for conjecture.

There is also another note written by me describing my interrogation by the SIB. I may possibly transcribe or transfer both the letter and these notes onto tape at some later date, but they do appear to me to be quite readable.

14 Steveton Close,

Bramhall,

Stockport,

Cheshire SK7 5PR

1st November ‘85

Dear Sir,

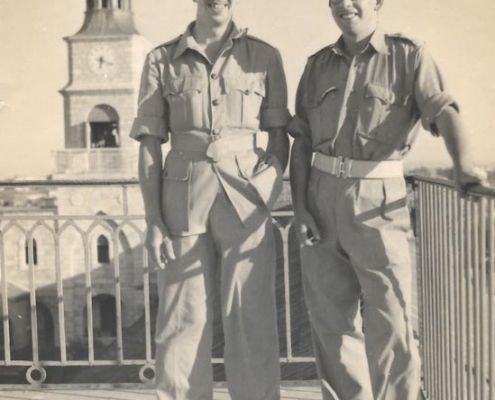

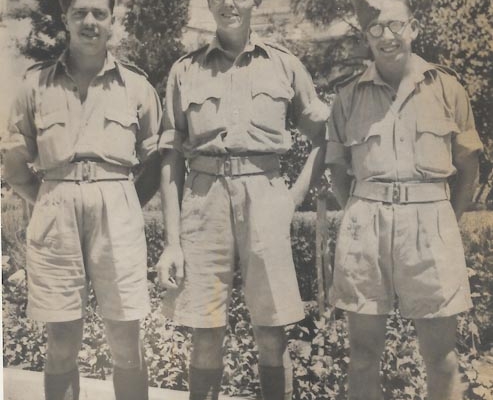

The recent case of alleged spying by service personnel in Cyprus brought back a vivid memory to me of some 41 and 42 years ago. I was serving in the Middle East with the RAPC as a field cashier. We were stationed in what was then Palestine and I, in company with some 20 others, were detailed for special duties in a place called Sarapand some miles from Jerusalem where we were barracked.

A race meeting had been organised, with the Veterinary Corps supplying the horses and riders and the Pay Corps contingent running the Book! If my memory serves me correctly, we were made up of NCO’s from the rank of Sergeant to Corporal with a couple of private soldiers put in for good measure. I was one of these. We started off with a float of £500, the book had an excellent day, but the takings added up to considerably less than what we started with!

Imagine the consternation? We were escorted back to Jerusalem under guard and marched into the guardroom where the Military Police took over. We were stripped completely, searched (our clothing) and after some time told we were detained in barracks until further notice and would be passed over to the SIB (Special Investigation Branch). For the following three weeks we were grilled at varying intervals during the day and night and always separately. The line of questioning followed a set pattern. One person being played off against another, saying that Sgt. So-and-So had admitted his guilt and naming you as his accomplice. You were then urged to tell all about his part and yours and your punishment would be less than severe. The personnel were disappearing one by

one and day by day and after some three weeks I was questioned for the last time and told that they knew I was guilty but pending further evidence I was released and a short time afterwards was posted to another country as was the other private soldier. The rest of the miscreants had been demoted and sentenced to the ‘Glass House’.

I was in fact innocent and it was only because of my resistance to pressure that I survived. Ironically, soon after my transfer I was promoted to Sergeant. Having followed the Cyprus trial closely it seems to me that the method of investigation must be satisfactory to the Service Chiefs because they don’t appear to have altered since my painful experience. To be honest, I was not subjected to any physical violence, only mental abuse. We were not at any time allowed a defence Counsel during the questioning.

I think this is the note to which my father refers in the second paragraph of this memory:

On the night of of May 31st I paraded with the rank of No.1 Platoon in the courtyard of the Syrian Orphanage in front of the gatehouse. The time was 18.20 hours and we were awaiting some instructions regarding a ‘Turn Out’. I was stood in the front of the rank and L/Sgt. Dobson stood next to me on m y right hand side. We were standing at ease and suddenly L/Sgt. Dobson commenced whispering to me.

The following is a record, to the best of my knowledge, of the conversation that took place between L/Sgt. Dobson and myself:-

He said, ‘I say, Burnett, did you cash a ticket with me when we were at Sarafand?

I said, ‘Don’t you remember whether I cashed a ticket with you or not’?

He said ‘Oh yes, I know you didn’t but the SIB have had me in and they asked me whether or not you had cashed a ticket with me. I knew you had already been in and I thought you might have said that you had cashed a ticket with me, so I thought I’d just ask you and if for some reason you had told them that you had cashed a ticket with me then I would go back in and see them again and say, ‘It slipped my memory before, Burnett did cash a ticket with me’.

I said ‘Are you sure you told them that I did not cash a ticket with you?’ He said, ‘Oh yes, they kept asking me and I repeated it three times, finally threatening to put in a written complaint to my OC if they didn’t stop continually asking me the same question over and over again.’

The conversation ceased at this stage and we were separated. L/Sgt Dobson has not spoken to me on the subject since, nor I to him.

Despite our somewhat straitened circumstances my childhood was a happy one, as indeed were that of my sister and brothers. My education was reasonably good and certainly better than the others, with perhaps the exception of Norman, who attended the same high school as I some three years previous to me and was due to some degree I suppose because it was uninterrupted from start to finish. If I were asked to describe myself as a boy, I would say I was a rather shy, introverted child who, being aware of this, developed a brash exterior to cover and above all I was a dreamer. I’ve always been more frightened and ashamed of not doing something rather than the doing itself. So, one might say that fright has always been the spur.

This has had its advantages ever since because I have never had a trade and consequently my working life has been extremely varied. It has always been my belief that qualifications are not always necessary and that if one is given the chance to do a job to prove oneself, success will often follow, but the initiative lies only with oneself.

The proof of this lies in the number of occupations I have undertaken. For example: labourer, internal auditor, door to door speciality salesman; Hoover salesman; repair man; auditor to the accountants; milkman; trainee store manager; regional manager; office manager; administration manager; chain store manager; promotions manager and not least self employed with a promising manufacturing business, defunct after two years’ trading due to lack of working capital and disagreement between partners.

I make no excuses for the sprinkling of the more mundane occupations and I do not want to give the impression that I’m ashamed of these particular occupations or that I despise them but I have never accepted Social Security and would do anything rather than go on what was described then as the Dole. Some of those positions mentioned stand out in my memory for one reason or another.

If I recall my job with Hoovers, at the rousing company song we had to sing at the regular pep meetings designed to infuse enthusiasm in our selling campaigns! I have never been very mechanical and I am at a loss to understand how I passed my training course before being let loose on the unsuspecting public in my dual role of salesman/repair man – and it was only after I had fused several houses and left the occupants in total darkness that I resigned rather than electrocute myself or a householder.

On a more amusing note, I went to one house to repair the cleaner and stepped into the hall, which was very poorly lit. It was very soft underfoot and on being taken into an adjoining room to meet my adversary – for example, the machine – the carpet felt even more luxurious, but an awful smell pervaded the atmosphere. I asked for more light but the lady made an excuse and retired so I searched in my bag for the torch, switched on, and saw to my horror that I was fetlock deep in excreta, animal I presumed, but I fled without further investigation.

(Paul Burnett) As I was putting this section together it struck me that something didn’t quite add up. My dad was born on 7th April 1920 and the young lad on the bottom row of the photograph is holding a sign which says Seymour Park, Class 3 1934. If you look at my dad in the pic, he certainly doesn’t look aged 14?

At the age of 62 I retired voluntarily, being unable to compete with the ever-increasing demand for younger men. After three months and the oncoming of autumn, Paul, my son asked me to work for him in his advertising business and take on the book work for a few hours a week.

This grew into three days a week as his business developed and it was only eight years later that I decided to finally retire. I’ve always been grateful to him. The work gave me a new lease of life and I would rate those years as some of the happiest of my working life. I like to think that my efforts were worthy of the remuneration paid to me and I’m certain that Paul always appreciated me.

We are temperamentally similar – somewhat fiery and with a short fuse, but we never seriously clashed. He has often said how much he envied me for the things I’ve done in my life and I’ve never been able to convince him that in fact the opposite is the case. Unlike me he has made a success of his desire to work for himself and on the social side he has engaged in pursuits requiring confidence and courage, for example parachute jumping, scuba diving, crewing tall ships, and skirmishing, to mention a few. It could be argued that the chance to participate in these activities did not come my way, but if it had, I’m not confident that I would have participated.

Paul also feels that he has been a disappointment to me in not taking up playing soccer. Every Father likes to think in the early stages that his son should automatically follow in his footsteps and be as good as he or better than his sire in the latter’s interests in his youth and it’s nice to know that in fact he has a mind of his own.

Anyway, to conclude on the subject I’m happy to think that maybe something of me has rubbed off on him and I’m very proud of him and his sister because they have both fully justified their upbringing by their mother and me.

(Paul Burnett) I really did appreciate him. His mathematical brain never ceased to amaze me so when he joined us at Burnett Blincow & Associates Ltd (BBA), he proved to be a tremendous asset to the team but particularly to myself and business partner, Alan Blincow. Numbers have never been my strong point so when it came to costing up all of the jobs which, at the time was done manually, he could work out percentage uplifts to outside purchases (usually a 33.3% uplift) faster in his head than I could do on a calculator. He refers to us both being similar temperamentally, we were. I recall a number of occasions when our voices became a little heated, usually due to the fact that he’d cost a job accurately according to physical hours worked and then I’d say that, that job feels like it’s worth another £100. He didn’t agree with that at all. He was a very honest man and would argue that it wasn’t fair. My take on that would be that I was charging for the invisible ‘pain’ factor involved in completion of the whole job.

He also refers to my football skills although he didn’t watch me very often. I can’t recall whether I ever told him but I played for the high school team usually on the right wing. I recall after one match I was approached by Mr. Boardman, our gym teacher who ran the team. He asked me if I would ever consider turning professional? I didn’t take him seriously so didn’t give it any more thought. Many years later I met a chap who I’d played against regularly after leaving school, who surprised me by saying he dreaded facing me when I had the ball. Naturally, this was great for my ego.

Finally, and this is maybe why he reckoned I didn’t posses the skills; I was playing a match in my mid 20’s and he came along with my young son Ryan to watch the game from the sidelines. I had the ball on the right wing, sprinted through to the opposing penalty area and cut in ready to shoot. I was abruptly hacked down and awarded a penalty. I placed the ball on the spot and took a few paces back. My plan was to look to the right, fool the goalkeeper and shoot to the left. Unfortunately, I was so keen on my amateur dramatics that as I ran up to the ball and kicked, my foot connected with the ground in front of the ball first, resulting in the ball trickling towards the goalkeeper who had to come forward to pick it up, otherwise it would never have reached him. I consciously looked to the sidelines where my dad and son were watching and I saw my dad looking down, shaking his head in total dismay.

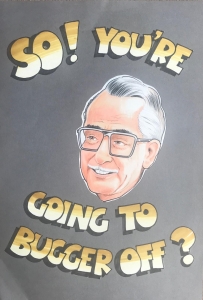

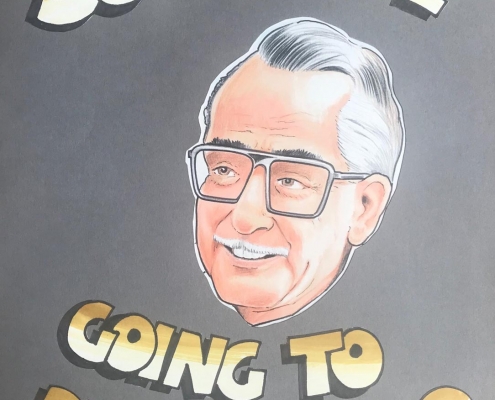

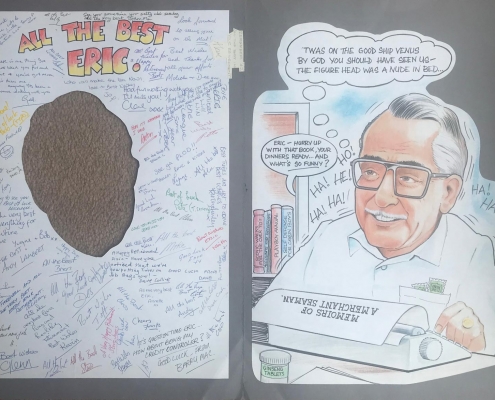

He finally decided to retire properly at age 70. I know he had made a great many friends in the company which some years earlier had merged with GBM and we became The GBM Group Plc. His retirement card is opposite drawn up by one of my talented colleagues Barry McCulloch. I, in fact we all, certainly missed him and will forever remember what a superb job he did for us. I consider myself very lucky as his son, to have shared those working years with him. I’m certain that not all father and son relationships have been as close as we were. He was my dad, my colleague and my great friend to whom I could turn to and discuss all things without fear or embarrassment and I loved him greatly.

The Hoover episode described on the previous page was the last job I had before falling seriously ill and which kept me from working again for exactly two years. The memory of this will never be erased from my mind because I firmly believe that I was the subject of a minor miracle. Minor is the wrong word, for a miracle is the greatest thing that can happen because only God can perform one and in my case in happened some forty years ago, but it is as clearly etched in my memory as if it were yesterday.

I was suffering from a bad cold and had gone out but during the morning began to feel unwell and decided to return home. I knocked on the front door, my mother opened it, and I fell in. She somehow got me to bed and sent for the family doctor. I was suffering some pain in my side and Dr. Duff diagnosed pleurisy and prescribed a few days in bed.

My condition deteriorated over a period of time and I developed a racking cough. The condition worsened and the doctor was called again. And looking back with hindsight I cannot understand why he didn’t get me into hospital. After a few days had elapsed I began to lapse into a state of semi-consciousness and my next eldest brother, Norman, who was married but living at home, decided that night to sleep with me. I cannot describe the nightmare that followed. All I know is that I seemed to have left this world and I was floating, but the effect was so fearful it was indescribable and had it not been for the close proximity of my brother I believe I would have gone. The crisis must have happened at the moment and I came too and fell asleep. Shortly afterwards I rallied somewhat, left my bed, and started walking about. The pain had gone but I was a shadow of my former self having lost two stones in weight and my hair began to fall out. I felt awful, and so weak, that I visited the doctor and told him how I still felt and that I couldn’t hold my shoulders back, upon which he replied, jokingly I suppose anyway, ‘Your overcoat must be too heavy’.

Joyce and I were engaged at the time, but her father was in some difficulty financially and the family had to sell up and move to Prestwich into a newsagent’s shop. The distance between us was considerable and she came to me as often as she could, but our relationship became less than happy due entirely to my attitude. My condition made me feel so wretched that I felt that I had lost my dignity completely. Joyce’s family became friendly with a young Jewish doctor and asked him if he would look at me. He said it was unethical, but he was persuaded. I refused when Joyce told me and only agreed after she begged me, and I went to his surgery. It took him only a few minutes to realise how serious my condition was and told me to see Dr. Duff immediately and demand to be sent by him to the Chest Clinic. The old doctor was not pleased and muttered something about young medics getting above themselves, but if I wished to go to the clinic I could go, but they would find nothing seriously amiss.

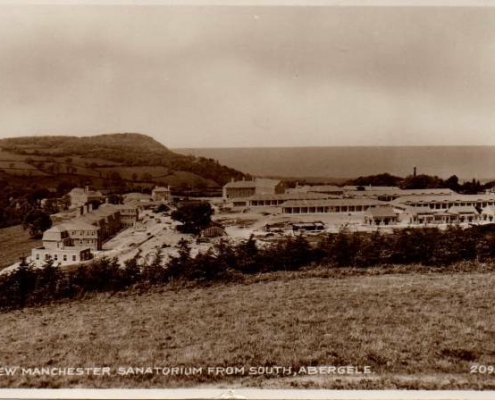

However, on seeing the specialist he said that the dry pleurisy had been correctly diagnosed but the condition had quickly changed to wet pleurisy and the cavity between my left lung and rib cage had filled with fluid and I would have to go into Abergele Sanatorium as I was potentially a tuberculosis case.

The young doctor in Prestwich had spoken, evidentially in rather serious terms, to Joyce’s father and he in turn persuaded Joyce to break off our engagement. I was extremely bitter at the time but have thought since that he thought he was acting in his best interests.

Within a very short time I was admitted to the Sanatorium and was happy to go because I wanted to get away from society completely and enter a world where everybody was the same as me. It seemed a strange philosophy, but I felt so low that I thought I would never be normal again.

I could write a chapter or two on my twelve months of incarceration, but I’ve gone on too long on the subject already. Suffice it to say that in the main, the year generally was a happy one, particularly the last six months. I was examined and told that I did not have TB, but the germs resided in the fluid and I would spend a lot of time completely in bed until the fluid disappeared. Only then would it be known whether or not my lung had been attacked.

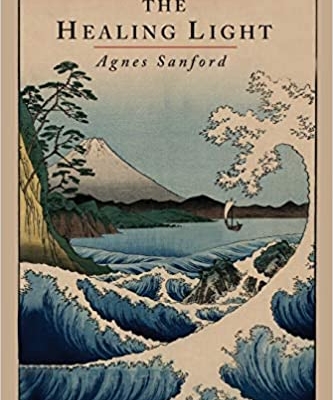

The cough persisted just as strongly but I felt better in my mind. My mother brought me a book entitled, ‘The Healing Light’ that a cousin, Lucy, sent to me with her love and good wishes and entreating me to read and believe. The book has never left my possession since. I read it every day and over and over again and followed its theme which was simply, ‘Ask God to come into me and His presence would drive out the illness and badness from me’. It would be some six months later, one evening before I went to sleep, that a voice in my mind clearly said, ‘You will awake in the morning and your cough will have left you’. I awoke in the morning and knew it would be so, and it was. My chest felt clear and free.

A day or two later the chief doctor did his rounds and asked me how I was. I just said that my cough had gone, and I felt very well. He sounded me, shook his head, and said, ‘We’ll take an X-ray’. Some two or three days later he sat on the side of my bed and told me that the shadow on my lung had cleared completely and had left no trace of scar and I could start getting up one hour a day. This continued and went into two hours, then five and seven and finally all day. My weight went from eight stone five pounds to nearly thirteen stone and I was put on a diet and sent home cured and very happy.

To conclude this long epistle, I must say that my bitterness towards Dr. Duff dissipated because he was old and evidently past his best, but he had been extremely good to my mother and very often did not charge her for his services. There was no National Health before the war. I’m more than happy to end this somewhat garbled chapter by saying that I found my ex-fiancée, wooed her and won her back and I love her now as I always did.

To finally conclude I was told by the doctor in the sanatorium that my condition was probably due to the years that I had spent abroad living in conditions that were not conducive to good health and culminating in a severe breakdown. Strangely enough my friend Derek suffered a similar experience in the early years of the war and was admitted to a sanatorium suffering from TB. He was cured in a shorter time than I but could not play an active role in the war ever again.

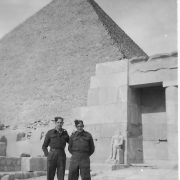

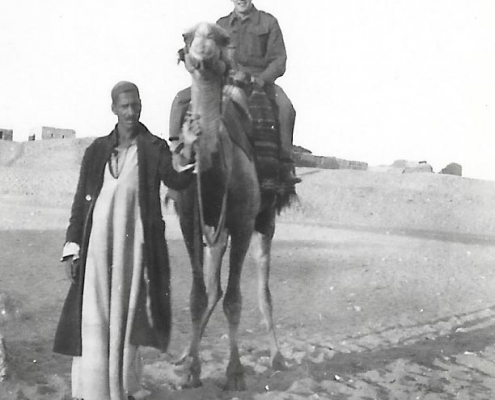

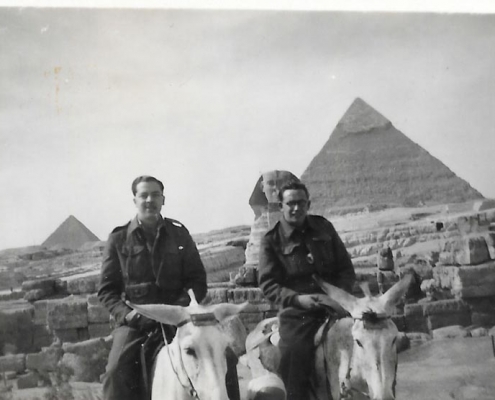

I set sail for an unknown destination in early February 1943. We were crowded like cattle in the troop ship and left Liverpool little knowing that we were to spend the next nine weeks cooped up in the holds of the ship and only allowed on deck for a limited number of hours during the day. We were bound for Egypt but didn’t know it of course, and I suppose the normal transit time would be two to three weeks. However at that time the Germans had the Mediterranean well bottled up and a troop ship would have been fair game so we had to go the long way round, for example, through the North Atlantic following the coast off the continent of Africa, into the South Atlantic, round the Cape of Good Hope, into the Indian Ocean and calling at Durban for our first and only stop to take on fresh water and provisions I suppose.

After a few days we sallied forth again via the coast, which we never saw, and into the Red Sea, and finally disembarked at Port Said. The journey out proved uneventful except for the occasional alert when a U-boat was in the vicinity. Conditions were pretty awful, especially during the night, because we were packed like cargo in the bowels of the ship, but it is surprising how one accustoms oneself to a situation and accepts the situation with resignation.

I hoped fervently that if we were attacked the torpedo would strike the spot on the side of the ship where I was sleeping and the end would be swift and merciful because certainly those who were not killed would suffer a painful and horrendous end. The chances of anyone reaching the deck was absolutely nil. The only means of access was via an almost vertical ladder into a hold above followed by a similar arrangement to the deck. Picture the scene, with hundreds of men in a panic attempting the impossible.

A vivid memory of the journey stands out in my mind. We were approaching Durban Harbour and I was on deck at the time but too far out to see the dockside itself when we could hear a woman’s voice singing, ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ and we thought it was the ship’s radio. It was only as we came in closer that we could see a figure in white holding a megaphone and saw to our amazement it was a woman with the most powerful voice I have ever heard. The attached cutting, which I found recently in a magazine, will describe the event more clearly than I could:

‘In full Voice’

Durban’s Lady in White by Perla Siedle Gibson, published by Aedificamus Press, price £14.95

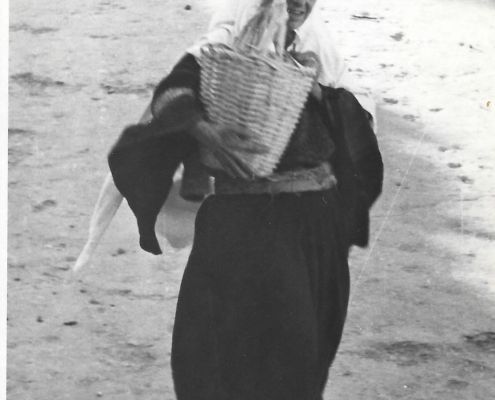

Any member of the Allied armed forced who passed through the port of Durban, South Africa, between April 1940 and August 1945 cannot fail to remember the Lady in White. The matronly figure of Perla Siedle Gibson, an opera singer, was something of an institution on the North Quay. Equipped with an official permit as a ‘dockside entertainer’ and a megaphone, she made it her business to sing popular songs as ships entered and left the harbour.

So dedicated was she to her self-imposed task of cheering up the troops, that she did not miss singing to one convoy in five years – not even the ships that sailed on the grief-filled day when she learned her eldest son had been killed in action. This is the story of the talented Mrs. Gibson’s full and interesting life, told in her own words. She wrote it in 1964, seven years before she died, but, until now, her autobiography has not been published in Britain.

Available from 113 The Ridgeway, Northaw, Herts EN6 4BG.

We were allowed ashore during the day and it was a blessed relief. We disembarked at Port Said and were almost immediately transferred onto a train for the journey to Jerusalem, and this was to prove a very uncomfortable experience. We were attired in tropical dress and shortly after we started, nightfall came. The Egyptian trains were austere to a fine degree. The window frames were devoid of glass and the seating consisted of a hard-wooden form and we were not to know that the desert goes freezing cold at night time. It was one of the longest nights of my life as we huddled together and waited for the dawn and for the sun to rise.

When the golden orb appeared on the horizon, we could feel its warmth immediately and our relief knew no bounds. On arrival we were marched to our barracks and then all hell broke loose. The garrison commander, a Major Binch, confronted our CO and in stentorian voice demanded to know whether he was out of his mind, and he said, ‘Get these men into battle dress and then report to me’. So began day one of what was to be an almost four-year stint. There would be many laughs and much misery and times when one gave up hope of ever seeing one’s mother and brothers and sister ever again. Fortunately, these morose moods didn’t last. We were all in the same boat and we learnt the true meaning of the word comradeship.

Apart from our duties in pay and accounts we were trained in weaponry and tactics designed to repel not the enemy, i.e. the Axis (we were too far away from the Germans and Italians) but to play a part in the defence of Jerusalem against the so called Stern Gang, at Urgun Zwar Lenunue, who were intent on Jewish independence and were taking full advantage of our pre-occupation with the war. The fighting troops could not be spared hence our involvement, together with the hated Palestine Police.

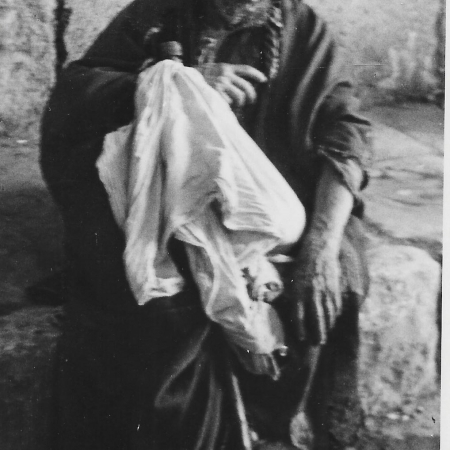

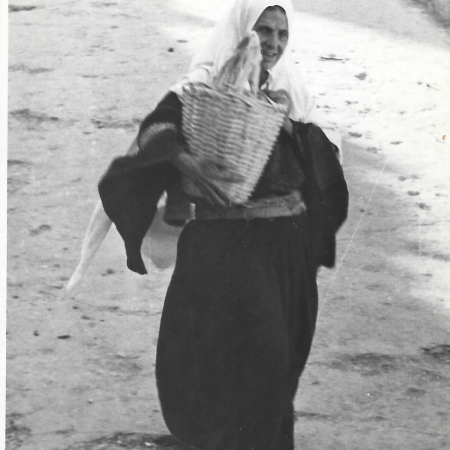

The Stern Gang would make sporadic raids from their hideouts in the surrounding villages and blow up communication centres, post offices, municipal buildings, ammunition dumps and anything that would hinder the British and cause havoc. One of their top men became the leader of the State of Israel and held that position for many years until 1991. His name of course was Menachem Begin. This man was the number one on the British wanted list of terrorists. It seems ironic to people of my age whose memories go back, that in his new position of respectability he continually branded Yasser Arafat and his Palestinian followers as terrorists because they wanted from him what he demanded from us – independence in their own country. However, we had little success. He blew into towns and blew out again and always disappeared despite our efforts to follow him. I remember on one occasion our officers thought we had him when we were sharply following his vehicles to a small village just outside the city. It was a small village in a hollow and we were stationed around the perimeter and looking down on the place. After 24 hours of boring inactivity the search was conducted but revealed nothing except the residents. Every so often a curfew would be placed, allowing the residents to come out of houses for only two hours in twenty-four. This was designed partly as a punishment because there were many anti-British, especially in the ghetto’s and old city, and partly to keep the streets clear in the event of a raid. We patrolled the streets to enforce the curfew and were frequently stoned by the children, who were sent out knowing they would not be harmed or taken into the police station, as would be their parents.

The Palestine police were, of course, entirely British manned and trained and were not always very gentle in their methods of upholding the peace, perhaps with good reason, I don’t know. People caught breaking the curfew were taken to a police station and paraded before the Station Sergeant, who sat behind a very tall charge desk. The average heighted person found his chin resting on the edge of the desk and craning his neck to look up at the Sergeant, a comical scene to us young soldiers.

After giving his particulars, was fined £2 Palestinian and hustled into a room, already overcrowded usually, and detained for 24 hours. With the passing of years and the gaining in maturity and watching scenes almost daily on TV of cruelty and ill-treatment of those who are not in a position to protest or defend themselves, I regret much of my lack of sympathy. Indeed, to quote an example, a classic case for arrest was to catch a person darting from his back door and running to the lavatory at the end of the yard. He had broken the curfew. Very amusing at the time, but not so funny in retrospect.

On one occasion I had a very close brush with death, but not at the hands of the enemy. I was doing a guard duty designed to prevent any unauthorized person from scaling the walls of our barracks and raiding the building which contained our weapons and ammunition. At the end of our tour of duty of two hours – two hours on and four off – we had to parade for dismissal and discharge the ammo from our rifles. The order was given to unload and press the trigger to confirm it. The man on my left pressed and I felt the wind of his bullet as it passed over my head and almost parted my hair. The miscreant of course paid the penalty and departed to detention, otherwise known as the ‘Glass House’. I often wonder how it would have been conveyed to my mother: ‘killed in action’ or just ‘accidental death’.

(Paul Burnett) Whilst on holiday somewhere in North Wales many years ago, Janet and I were wandering around a small craft village. A small enterprise suddenly caught my attention as I could see that this gentleman would take medals and cap badges and then mount them in a wooden frame of your choice. My dad had given me his medals some years previously which I was very grateful for. However, they were stored up in the loft with other items he had passed over to me as he knew I wanted to preserve them for the future. I arranged there and then to forward the medals to him by courier which I did on returning home. A few weeks later this mount arrived and I was particularly pleased when I handed them back to my dad for his birthday. It brought him to tears (me as well) but he kept it on the wall of his study until I inherited them once again after he passed away.

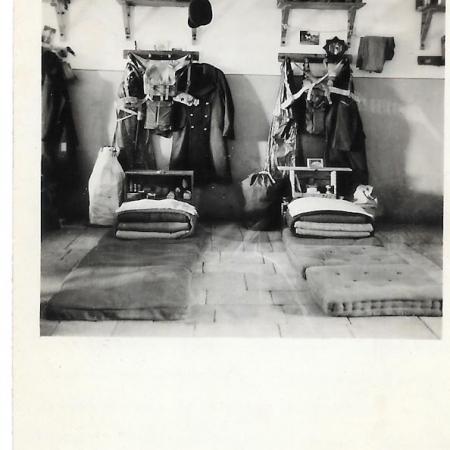

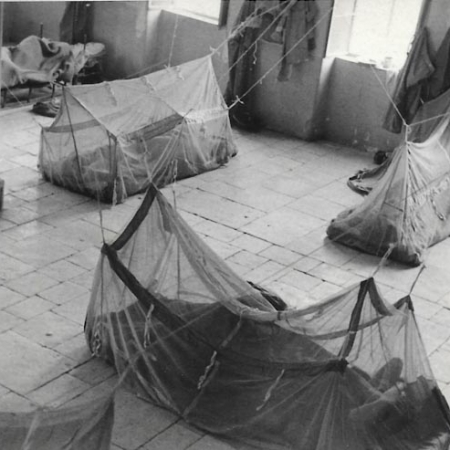

After nearly four years and almost a year after the war in Europe had finished, I received my notice of demobilization and returned home. Had it come much later I doubt very much whether I would have been in a condition to go home, for many weeks I spent practically every evening in the Sergeant’s Mess. We were stationed in a deserted spot near the Suez Canal and life had become very boring. There was very little activity and our morale was at its lowest ebb. As a Sergeant I enjoyed infinitely better conditions than those below me. I had the luxury of a room to myself with a dhobi wallah to launder my clothes and clean my room and make my bed. Yes, I had a real single bed.

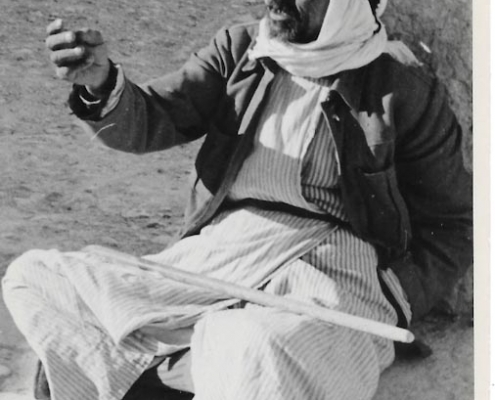

My daily help was an Egyptian of course and his name was Abdullah. His chores were as described, and he commenced his duties early each day by fetching me a cup of tea before I got up. Like most of his countrymen he himself lived in abject poverty and scraped an existence by preying on the unwary traveller. For example, the British Tommy and other soldiers of whatever nationality. One suffered most for the first few months as a rookie after arrival in the Middle East, during which time one was bitten several times until the lesson was learnt.

After nearly four years and considering myself immune, I fell heavily to the wiles of Abdullah. I paid him fifteen piastas a week for his services. Not a lot, but about the going rate. One morning he had the effrontery to ask for a rise and I told him the only rise he would get would be when his feet left the ground. This turned out to be a grave error of judgement on my part. A couple of days before I was due to leave for home Abdullah left my employment without giving notice and took most of my possessions with him. I searched the camp, together with the Military Police, and eventually found him. He was given the customary treatment by the MPs, but there was no trace of my belongings. There is a moral to be learned here: never turn down a request of so little magnitude unless one is completely invulnerable. The cost to me would have been about a couple of pence old money.

However, to continue, life was very boring and in the late afternoon when our labours were over I retired to the Sergeant’s Mess for a meal and spent the evening carousing with my fellow NCOs. The Sergeant’s Mess is almost a holy sanctum and the Senior NCO, usually a regimental Sergeant Major, ruled with great authority, and officers, unless on Army business, only entered by invitation and woe betide anyone who forgot to remove his cap before crossing the threshold.

We drank at the bar, played table tennis and cards, argued and debated, and always listened when the RSM held sway, no matter how boring he was, and he very often was. Quite frequently the RSM would organize one of his special evenings. The table tennis table would be literally covered with bottles of beer and on his instructions, nobody was allowed to leave the Mess until the table was cleared, and on more than one occasion I crawled to my room on hands and knees. I could describe more lurid evenings in that Mess, but they’re better left unsaid.

Shortly before leaving for home my CO asked me if I would be interested in a commission, and if so, he would recommend me. He told me it would mean going to the OCTU, which is the Officers’ Cadet Training Unit, after I had spent a leave and then returning for duty as a lieutenant paymaster on the troop ships bound for the Far East. I gave it some consideration and decided against.

I had been away too long, but on my arrival at Dover, in bitterly cold weather and after an horrendous Channel crossing when the waves rose to the height of a modern house and the troughs were equally as deep, this, together with the reception we received when trying to make a life for ourselves, made me doubt the wisdom of my decision and anyway the Japanese war didn’t last much longer, so the situation would have been the same, and I’m sure that the fact that I had been an Officer wouldn’t have helped me because they found the situation no different, and who knows, I might not have been as fortunate in that extra period of service as I had been in the previous.

(Paul Burnett) This completes my dad’s book ‘The Ramblings Of My Mind’. He spent many hours writing this over a long time. I cannot remember how long and indeed whether it was over the space of months or years but I know he enjoyed writing it immensely. He spent his latter years in a retirement flat with my mum but I know he regretted moving from his bungalow on Warwick Drive in Hazel Grove. He called the flat ‘God’s Waiting Room’. I believe the main reason he decided to move here was that he was finding it hard to maintain his garden; it might also be the fact that he needed to raise some money from the sale of the bungalow in order to subsidise his state pension.

My dad passed away on 8th May 2002 and it has taken me 18 long years of feeling guilty that I didn’t publish this precious story much earlier – especially as it was I that asked him to do it for me originally. Although I spent many years in advertising, I have never been very technical. In fact, it has always been a bit of joke between myself and my very creative colleagues that I always struggled to ‘get stuff to work’. I want to thank Chris Place chrisplace.net who was best man at my wedding and mentor during my skydiving years. He remains one of my closest pals. It was he that offered to actually produce this site for me but that is not what I wanted. Instead, I asked him if would spend a few hours with me and try to get me started. He did and continues to help as I have been learning as I go along. I know it’s not perfect but I have succeeded in getting it to this stage.

As time goes by, I hope to improve my web building skills and may return to this section with a view to improving it at some point in the future. To those who read this, I really hope you enjoy it. I know there are many unwritten stories that my dad didn’t get around to putting down on paper. One of which I mentioned earlier in my ‘About’ introduction. It involved the throwing of a hand grenade (my dad was mainly right handed but for some strange reason threw with his left hand) which sent the rest of his platoon diving for cover. Alas, it isn’t written but this story and others will remain in my memory forever.

Thank you for taking the time to get this far.

Paul Burnett (5th May 2020)